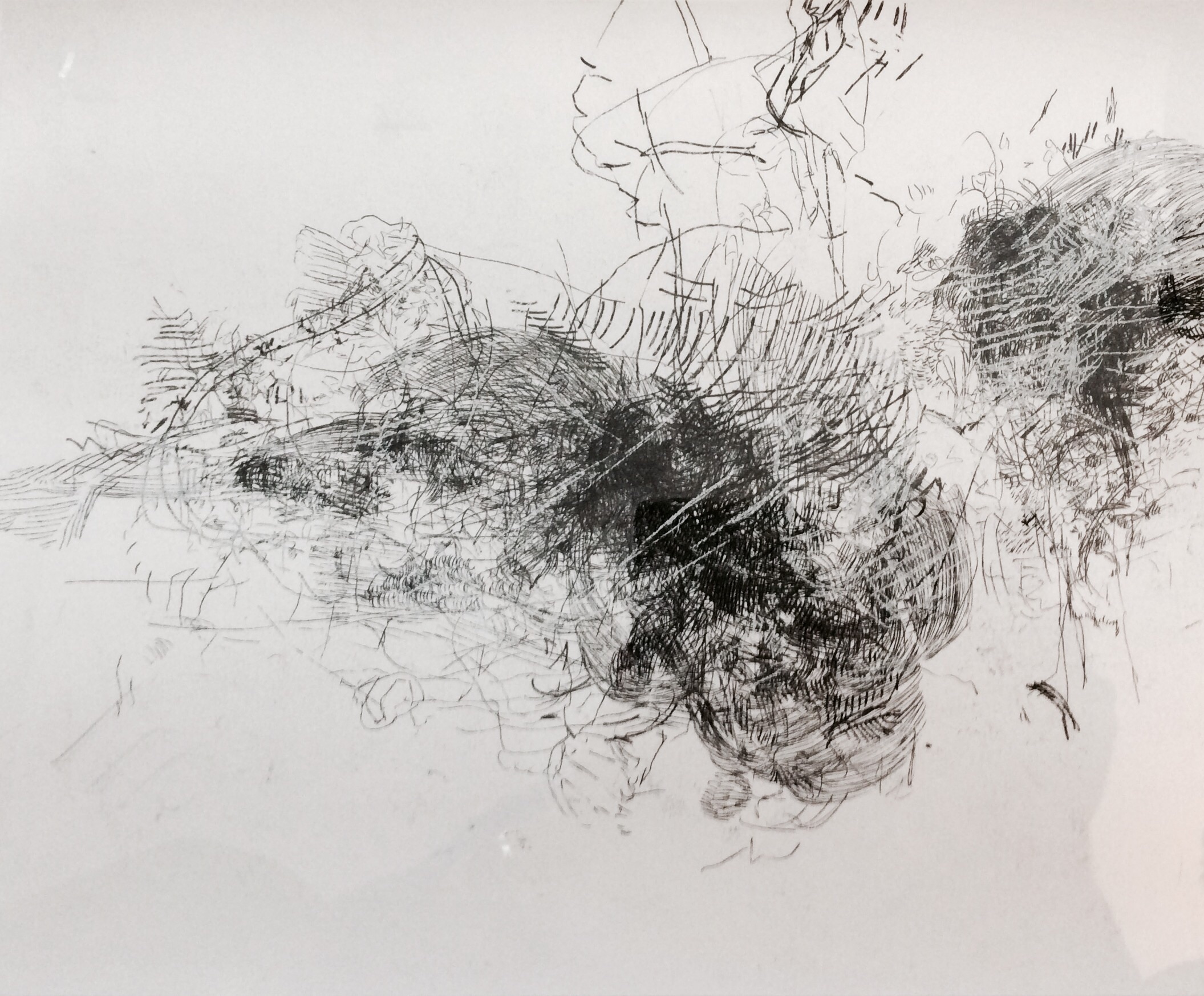

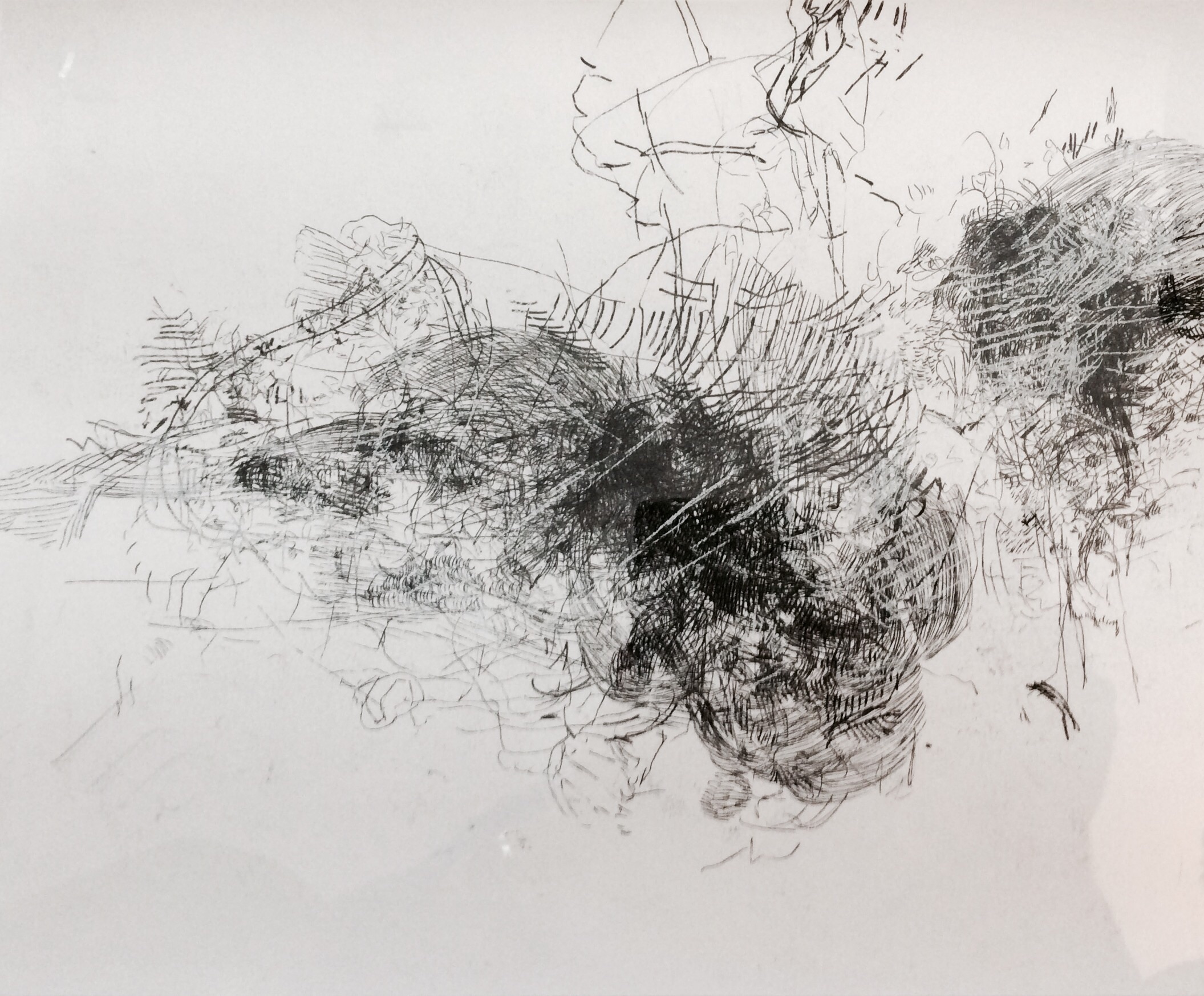

Hedwig Broukaert is a terribly exciting artist from Belgium who moved to NYC. She simply has incredible drawing talent. This particular drawing from a series of three is mindboggling, there is a form which in detail denies to be a form. When you try to decipher the details or try drawing it yourself, you will understand how difficult it is to master this balance act. I’m happy to include her in my collection. The above work is called “Untitled”, was done in 2014 with white and black transfer paper on paper (30 x 36,8 cm).

On her website she posted this review which obviously made her proud, further to this a small review in the NYT:

HEDWIG BROUCKAERT

a knot, a tangle, a blemish in the eternal smoothness

by Taney Roniger

KENTLER INTERNATIONAL DRAWING SPACE

SEPTEMBER 12 – OCTOBER 26, 2014

Our postmodern sensibilities notwithstanding, there remains in this culture a deep and pervasive undercurrent of Platonic idealism, of belief in the possibility of purity, perfection, and permanence in a world that so emphatically suggests otherwise. Long since unleashed from its religious origins, this inclination toward transcendence and its agents of perpetuation today assume many guises. For Belgian artist Hedwig Brouckaert, the mainstream media is a most conspicuous purveyor with its relentless propagation of idealized images of the human body. In her current show, Brouckaert’s thematic focus is on hair—both as depicted in the media as a symbol of youth, vitality, and sexual power and as a personal token of our mortality—in a body of work that presents a powerful challenge to this idealist impulse. An artist whose practice is rooted in drawing, Brouckaert uses the physicality of her medium to make her conceptual case, deftly manipulating linear forms and materials to embody as much as they represent.

Hedwig Brouckaert, Detail: “a knot, a tangle, a blemish in the eternal smoothness,” 2014. Magazine clippings, pins, wire, hair; dimensions variable. Photo credit: Etienne Frossard.

Drawing on the poetic potential of understatement, the show comprises just two works: a large-scale triptych of works on paper that hang scroll-like from one wall, and, in an alcove on the other side of the gallery, a looming sculptural installation. Radically different in mood and materials, the two create a palpable tension. Any apparent dissonance is short-lived, however, as careful scrutiny reveals that the two works are in fact intimately—and provocatively—related.

Enticed by its sense of expansiveness, one inclines first toward the triptych. In “Uprooted I,II,II” (2011), dense clusters of delicate, hair-like lines float across three towering sheets of unframed paper, some attenuating to barely visible dust-like particles. The negative space speaks first, however: huge swaths of the paper’s pristine white surfaces have been left untouched. This evocation of purity and the metaphysical realm is further suggested by the ascending thrust of the forms. But for the strange nature of the forms themselves, the piece could be mistaken for an uninflected cloudscape. Examining the skeins of linear marks, which resemble soft graphite but which are in fact carbon residue, one discerns patterns and textures decidedly sourced in human hair. Long and flowing, gnarled and matted, loose and wayward—intimations of the beyond notwithstanding, these forms are clearly rooted in the human body. Other than this allusion to corporeal existence, there is little evidence of the artist’s source material or process in this piece, so thoroughly has the former been transformed and the latter muted.

Across the gallery, however, both latent elements come to the fore with visceral impact. In “a knot, a tangle, a blemish in the eternal smoothness” (2014) Brouckaert’s clusters acquire three-dimensional form. Here, dense agglomerations of cut and crumped paper bound together with wire, steel pins, and hair (the artist’s own) protrude from the walls in irregular patches, rising up to and infiltrating the ceiling. Close inspection reveals that the paper masses are layers of glossy magazine clippings that have been delicately excised, abraded with some kind of sharp linear tool, and stitched together into tight bundles that overall assume an earthy brown hue. While fragments of faces and illegible bits of advertising copy can be detected, the majority of the printed imagery is of hair running the full gamut of styles and colors. If the ascending composition echoes the metaphysical leaning of the triptych, everything else about this piece bespeaks earth and body. Physical sensation is evoked throughout by the repeated piercing of the skin-like paper and the strands of loose hair that hang from forms that read as decomposing organic matter. Dense, complex, and emphatically unclean, this piece teems with the raw energy of nature uninterrupted by our ideas of how it should be. Seductive and repulsive, enticing and terrifying, it exudes mystery—and richly mirrors the full range of emotions we have about our own embodiment.

Were it not for one subtlety, one could mistake the two works as presenting a simple dialectical tension. However, the linear grooves scored into the magazine paper reveal that the raw material constituting the earth-bound piece is the origin of the linear marks that float across the ethereal triptych. With carbon paper sandwiched in between magazine page and drawing paper, the artist has used a needle to inscribe lines from the hair on the magazines’ images. The latter’s distressed remains become substance for the sculptural work. By way of intense physical contact—cutting, scratching, “decomposing”—enacted over expanses of time inimical to today’s consumer culture, Brouckaert wholly transforms her banal source material, imposing on it a dimension of existence that its entire enterprise is built on denying: that of the real.

With its insistence on the primacy of the real, Brouckaert’s work is also a plea for the recognition of a kind of beauty too little acknowledged in contemporary culture: that which can be found in the very things we are conditioned to repudiate. Imperfect surfaces, forms that defy easy comprehension, bodies vulnerable to decline and decay—why must our aesthetic ideals reach beyond the things of which life actually consists? Why, when we undeniably live in this world, do we continually appeal for meaning in the “elsewhere and otherwise”? Brouckaert’s work doesn’t seek to answer these questions, but it does bring the words of Wallace Stevens to mind: “The way through the world is more difficult to find than the way beyond it.” This show compellingly challenges us to do the more difficult thing.